The day I visit the Cyberhive, I take a taxi downtown to escape the rain. Outside, there in no horizon line, just still blue mist, slow grey fog, white melting rain.

When I arrive, I leave the waterfront behind and step into the hive. Inside, the heavy fog outside fractures into a thousand new sounds, spaces, motions. In the place of wet/damp monochromes, I meet a chorus of:

Buzzing humming tinkling rushing swarming testing brewing making tasting lingering flashing trembling working waggling thundering mingling tingling aching tickling

I meet:

Combs covered wires out fuzzy backs long limbs painted resistors fast flying larvae hatching lights reaching slowly liquid lapping faces touching lines dancing buds gathering feeding bringing sweetness processing pollen matriarchs moving assembling dissembling beginning again

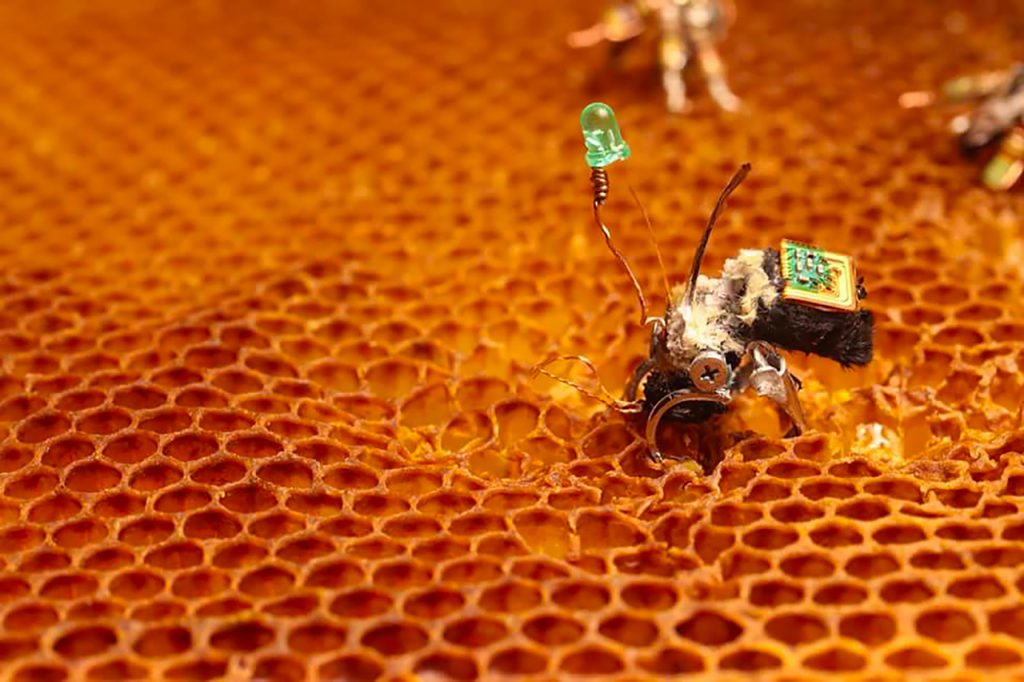

That is to say: I meet Ruth. Ruth Marsh is a multidisciplinary artist who, for the past several years, has been creating the speculative future that is the Cyberhive. In the iteration I witness, the Cyberhive is an immersive cinema experience staged in the Sea Dome at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic. The screening is presented by IOTA Institute, who hosted Ruth for a two month residency to make work specifically designed for the dome. Cyberhive is a stop-motion animated film—part documentary, part sci-fi—that records the activities of cyborg bees living in a cybernetic hive. Directed and produced by Ruth, the film features a original music and sound design by Jeremy Costello and technical direction by Nick Iwaskow. Without narrative, human language, or logic (as we define it now), Cyberhive imagines a dystopian post-apocalyptic landscape that exists within the confines of a bright, psychedelic beehive. In it, bees are born and re-born as hybrid beings, consisting of technological debris and natural bee skeletons. They are the remaining survivors of the global bee population, decimated by humanity-induced environmental decline.

The bees in the film are real. Since 2011, Ruth has been creating a series of artworks focused on bee disappearances. She works with found dead bees obtained through a community-engaged project of collecting. Hundreds of dead bees have been mailed to Ruth from people all over Canada, both friends and strangers. Using social media as a rallying point, Ruth kindly asks: “May I have your bees, please.” She then mindfully and meticulously repairs the dead bees, re-animating them through cyber taxidermies, stop motion animation, and taxonomies of care.

As of last count, the cyborg bees number around 500. The bees form the basis of Ruth’s current practice, and have been fixtures in several recent projects including “Ideal Bounds,” an exhibition at Struts Gallery & Faucet Media Arts Centre, in which the bees are presented as preserved relics in an imagined future dystopian museum. In this staging, the bees are read as traces and tributes of an environment long past, as the fossilized bodies upon which histories and fictions alike may be cast. Like the specimens at the Museum of Jurassic Technology, cyborg bees are elegies to both the real and imagined beings they stand in for, the beings who became consequences and cautionary tales of environmental loss.

—-

In the dome, I become part of the hive. Not quite a worker bee, but not quite an interloper. Rather, much like the bee themselves, the experience of the viewer is something hybridized—something caught between being part of technology and being witness to it. Once inside, time and direction dissolve, become distorted as horizons expand and envelope me. The temperature drops 10 degrees, the climate control a tool to keep the dome taut and seamless. A felt departure from the thick humidity outside. Five hidden projectors animate the space, and take my surroundings from blank white sheets into bright swirling glittery combs, tiny limbs scurrying to-and-fro, on a mission, with some message. I turn my head to follow the hive turning slowly around me. What were once tiny hive models made of wires, circuits, Christmas lights and resistors, are, on the dome screen, galaxies of comb terrain and swarming life. Where once the artist was the agent, crafting and creating little life forms, in the dome the roles are reversed. The hive builds around us, rendering us small, part of the flow, subject to transformation.

���-

There is no language in the film. In its place, Costello��s pulsing synth simulates bee communication, concocting a language of pheromones, feelings, and purpose. The wordlessness of the bee’s language reminds me of what happens when language breaks down, when communication fails, when we know which words to use, but not how to apply them. But it reminds me, too, of when words are not enough. I ask myself: “what can I do? What is useful?”

—

The bee’s world, and Ruth’s by extension, is one of emancipatory transformation and radical fictions. It is a feminist world, and a queer one, where matriarchs reign and multiplicities are given. It is, in other words, an inherently political world, though the film makes no explicit reference to politics or political structures. But in their very existence, the cyborgs are a mark of resistance, of resiliency, of care as labour, and labour as care.

And indeed, care and labour are, in the bee’s world and in Ruth’s, inextricably joined.

The bees are programmed—both naturally and technologically—to labour, to produce and build. The urgency of their tasks are palpable, felt through erratic motions, twisting light lines, looping waggle dances, antennae kisses. They move rhythmically through cycles of production, building networks that are at once social, environmental and technological. As I watch in dome, becoming increasingly disoriented in time and space, the bees move around me with singlemindedness, with purpose, with pleasure.

But despite the bee’s programmed directive to produce, a question hovers above the hive: to what end does this production serve? And what does production and productivity mean in a post-apocalyptic post-capitalist feminist future? What does it provide, who provides it, and how is it useful?

I am tempted here to think of a currency of care. Like Sara Ahmed “affective economies”—in which affect is conceived as a personal and political atmosphere that circulates between groups and individuals—care is similarly transferred and felt. In the Cyberhive, care is communicated through labour, moving between cyborg and environment, demonstrating a reciprocal commitment to survival and sustainability. In building the hive, and in building and re-building themselves, the bees enact a spirit of radical resiliency and a commitment to each other.

Beyond the hive, but still embedded in it, the same care circulates between Ruth and the many communities involved in this project. Though the act of constructing the bees and their hives is a deeply solitary act, community care is present in each phase of their transformation: it moves from the strangers and friends who send bees, to Ruth as the cyborg architect, and to the dead bees, soon to be re-born.

In A Cyborg Manifesto, Donna Haraway writes of the “the pleasure in the confusion of boundaries” and of “the responsibility of their construction”. Creating the Cyberhive, Ruth mindfully and joyfully skews the boundaries of care / labour / individual / collective / organic / technological, and imagines a world in which the value of labour is not in the product, but in the act—in fact that we care enough to act at all, whether it is useful or not.

—

Alone, and on a second viewing of the film, I test my disorientation and try to walk around the dome. I find myself hesitant, in a virtual reality, afraid that a missed step may throw me into an errant bee, into a speculative future, into a cyborg self; afraid that I might not mind.

The dome changed the scale of Ruth’s work, expanded the scope of its worlds and realities, and turned a solitary practice of making into one of collaboration. Turned it into a collaborative practice of seeing and feeling.

I leave the hive and walk back out into:

still blue mist felt air fast slow fog coming legs leaving deck receding white melting rain hesitating

remembering and feeling still:

quick humming bright magic music soaring swarming landing buzzing combs fuzzing pollens building backs aching assembling dissembling beginning again

[1] Ahmed, Sara. “Affective Economies.” Social Text 22, no. 2 (2004): 117-39.

[1] Haraway, Donna. “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century.” Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. (New York: Routledge, 1991). 149-181.