You use the encaustic method of colouring heated beeswax with powder pigment to create your ‘paint’, a process dating back to 500 BC, where it was initially used in Greek naval architecture and, in the history of Western art, famously implemented in funerary portraiture in the first century AD of Coptic Egypt. Does the time-consuming and purist nature of this method play into the underlying concept that drives your practice?

It’s interesting that you used the word ‘purist’. True, encaustic is pure in the simplicity of its elements: beeswax, as a solid, organic material, is warmed up to liquefy it, and then powdered pigments are added. The more pigments mixed in, the more opaque the ‘paint’ is. Colours are either cross-mixed in the liquid wax itself or in the application of one semi-transparent layer over another in the painting process. I treat encaustic as a ‘thick watercolour’ where surfaces can be coated but information from the substrate is still evident.

Encaustic is time consuming to prepare. It also takes years to understand how the different pigments react with the wax. And how to control the ‘burning in’ stage where the painted wax layers are reheated to fuse them into a singular body (the term “encaustic” loosely relates to this reheat/burn-in phase). Once the prep work is done, the actual painting process is fast and, for me intuitive, since different brushes lay down different thickness layers of wax that affect the outcome of a painting. I also can only apply 4 to 6 inch brush strokes before the wax is either depleted from the brush or cooled down and unworkable.

In some ways, I think of my use of encaustic as a form of ‘anti-painting’ since it is not focused on my virtuosic manipulation of paint squeezed from a supplier’s tube, mixed on a palette and then applied onto canvas with brushes – but more about the management of a series of wax-coating systems. In recent works, due to the ‘burning in’ process with an electric heat-gun, my brush strokes are obliterated as the wax is melted to a complete liquid state that then soaks into the paper substrate as much as the physical surface allows. I manage and edit the results and add and subtract layers as needed. Again, I don’t think of myself as a painter but more as a skilled applier of codified wax-based coating materials.

In You are Here (2005), you’ve created a large grid from pieces of envelopes and mail addressed to you and to individuals from the arts community, collaged together and painted sparingly with various blues. When installed together, the blue becomes a body of water, detailing a map of the extended environs of Halifax Harbour, specifically. A red painted area “marks the spot” stating that “you are here”. By doing this you juxtapose the self onto the site; wherever the work is the viewer is placed into the map, nearing the semblance of participation. Why do you think humans have an innate need to know where they are at all times, and do you aim to displace this need or give it roots?

This is a big question that speaks to multiple meta-narratives. One is how ‘mapping’ and spatial information has become visual shorthand to illustrate the dialectical gap between Modernism and Postmodernism. When I was in in elementary school in the 1960’s, maps represented empirical evidence of how the geo-political world was constructed. There was a fixed frame, a Modernist author/publisher (and authority), a ‘centre of the world’ (always North American from a Canadian/American point of view), with projection systems biased toward the Northern, Euro-colonizing nations, complete with colour-coded countries, etc.

Postmodernist maps no longer have fixed frames and are synonymous with digital culture and satellite fluidity where the centres of the world are now individual cell phones, their GPS coordinates and the world that radiates out from the reception point of a cell signal. No meta-spatial framework exists other than the infrastructural support created by Google Earth (which is another form of First World colonization…)

My 2005 You Are Here illustrates a rethinking of how these worldviews are constructed. The piece is built on traditional mapping framework with a fixed graphic depiction of Halifax and its environs. This includes a centre, the red envelopes that represent Pier 22 where the work was initially installed as part of the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia’s summer project titled Art Port.

But 2005 was in an era before smart phones existed. Back to meta-narrative – all of the envelopes in the piece are those that were mailed to me by a host of senders, for example: professional art-world promoters, banking agencies, work-related envelopes, family holiday wishes, fundraising and charity outreach. In all of these cases, I was their ‘object’ of social, political and economic interest, often unsolicited by me. I use these envelopes, however, to document my life and my relationships through the creative process – and in the process, I am subject in, and author of, the resulting work.

Your question: “Why do you think humans have an innate need to know where they are at all times, and do you aim to displace this need or give it roots?” Humans want to know where they are in the world but most importantly in relationship to each other. So I archive and curate my network of social, economic, and political connections as witnessed by accumulated envelopes, notes and lists, a process that is known as ‘passive mapping’, something I learned about at a conference in 2008 in Vienna about the intersections between art and cartography.

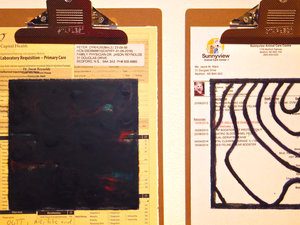

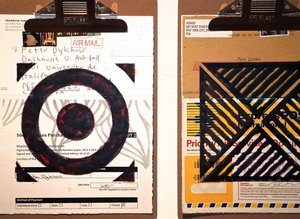

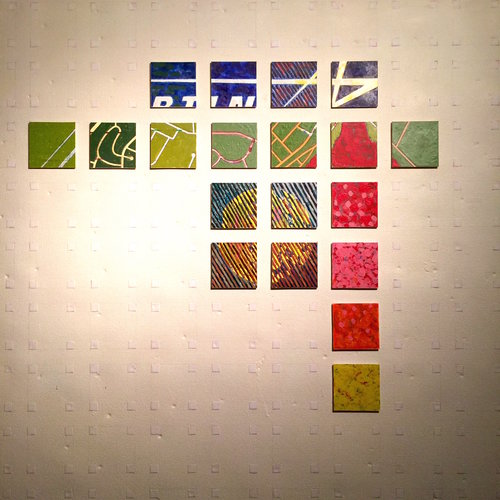

Papers, lists, notes, envelopes feature prominently in your work like in Peripheral Traces (Dark Heart) (2014), in which you collected papers relating to three relevant categories of your life: Home Front, Work Force and Art World. We will often see addresses, either to you at your gallery or to individuals that together shape what you describe as a type of “sociological sampling”. You’ve explained that you use a standard size square panel to assemble your grids due to cost and efficiency of materials. You also incorporate shipping receipts and communications regarding the trajectory of artwork and exhibitions in an almost didactic manner. Is there an element of apathy or dispassion that can be traced through the work, especially in relation to the economy of art presentation or the redundancy of everyday chores?

I do not like to make arbitrary choices that rely on personal taste but prefer to find pre-existing structures that reflect conditions in the ‘real world’. So a clipboard is a somewhat global object that comes in two sizes: standard and legal. The ‘standard’ clipboard is designed to accommodate both European stationary (which is slightly larger) and the North American 11” x 8.5” sheet. All of the envelopes, notes, and lists that I harvest are from standard issue industrial products that relate, in one way or another, back to the 11” x 8.5” module. Even the coloured block of note papers from Staples have a palette that is pleasing when sheets are mixed together. These industrial conditions interest me and become evidence of how our global, neo-liberal world operates.

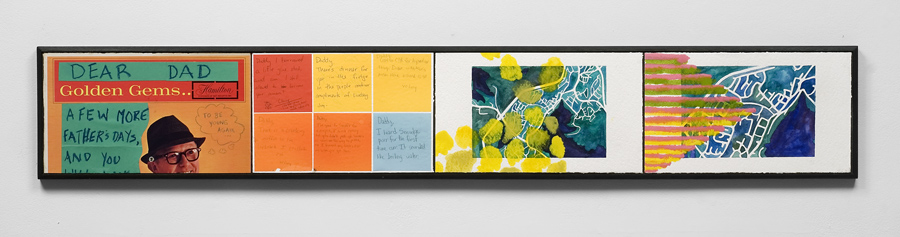

“Is there an element of apathy or dispassion that can be traced through the work, especially in relation to the economy of art presentation of the redundancy of everyday chores?” This, again, is a good question. I’m fascinated about how ‘art and life’ can form a creative bio-loop of sorts. I accept the paper substrates as a condition of our world as we know it. But am also interested in the micro-narratives of human life as witnessed by shopping lists, car repair reports, ‘to-do’ work lists, notes between family members, co-workers, etc. The notes that I author become a dispassionate diary of sorts while the documents written by others form a portrait of the banality of my life.

When I first started collecting envelopes addressed to me, I archived everything with my name on it. After a few years of this, and an ever-accumulating stack of full tote containers, I was afraid of becoming an irrational hoarder. Early pieces such as You Are Here and Pressure Today featured both mechanically printed labels as well as handwritten ones.

By 2012, I no longer felt the need to collect the mechanically printed envelopes that were often from corporate and business oriented senders. So I recycled those and now only collect envelopes, lists, notes, etc., that are handwritten. In an odd way, it prioritized the human touch and the personal signature, the uniqueness of penmanship, and the graphic social fingerprint of the author.

In Peripheral Traces (Dark Heart), I curated the envelopes, notes, and lists according to social aspect of my life – and the superimposed dark square in each was based on a codified graphic.

Home Front reflects communications about my domestic life with my spouse and daughters and cats with the overlaid graphic representing contour lines of isobars in barometric pressure maps, the visual harbinger of changes in weather systems.

Work Force captures material from my ‘day jobs’ with the central square alluding to stock market graphics and other images of economic indicators. Art World represented material from personal friends and colleagues engaged in art practice and featured fanciful modernist ‘symbols’ as an overlay.

The square and the grid in art, most closely associated with modernism, always feels relevant (see Rosalind Krauss’s essay “Grids”): Piet Mondrian’s geometric grids, Robert Ryman’s continuous variation on the white square, Kazimir Malevich‘s grounding black square. Even in our everyday, the making of lists and inputting data into squares on a calendar constructs order, like in your Clipboard Grids. Even though your work is more linked to the proportionate scale of cartographies than constructivism (See Ilya Kabakov, The Schedule for Taking Out the Garbage Can 1980), are you using the grid and the square in relation to these art histories?

Absolutely. My three favourite modernist artist/artworks from the 20th century are Malevich’s White Square, any of the classic Mondrian Compositions and Jasper John’s American Flag that is, ostensibly, a grid of stars inside a field of stripes. Each one of these works were also resolutely hand-painted with John’s use of encaustic critical in its semi-transparent superimposition of symbols that ‘represent’ a flag over a field of ripped and torn newsprint.

Ultimately, though, I think of the grid as the graphic expression of the binaries built into Western philosophy. The Cartesian grid of x/y coordinates is a pre-modern example. Which led to the mapped gridding of the 3D globe into the 16th century 2D Mercator projection, a system that prioritizes the northern hemisphere and is now synonymous with the creation of navigation trade routes for European colonizers. It is the reason for long, straight boundaries such as the 49th Parallel and perfectly rectangular American states that do not reflect the geographies of the landscape. (In this projection, Greenland is illustrated as the same size as Africa when, in reality, Greenland has less than 1/10th of the landmass of Africa.)

The grid is both villain and practical spatial organizer. And I like that tension.

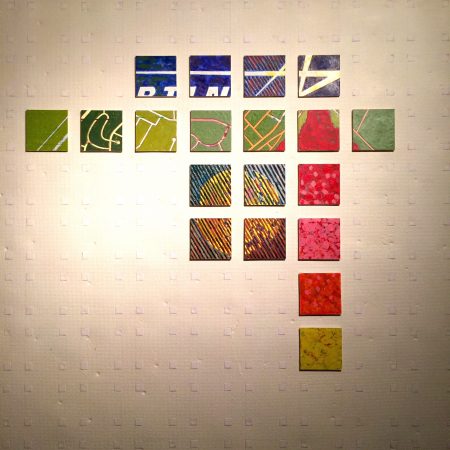

In art-making though, particularly painting, each panel in one of my gridded composition is but one component of a larger whole, and as a single unit is expendable if not successful within the work under construction. The studio narrative, then, is not about my heroic studio engagement/battles with paint in the arena of a single canvas. Rather, it is about the systematic, scaleable construction of an image that can expand and contract as desired. Or dissolve and reconfigure into new works. Indeed, I’m in the process of completely renovating Your Are Here and transposing it from 49 sixteen-inch panels onto 196 six-inch units. Other pieces will be decommissioned with the best components slated for re-use into completely new works.

You’ve mentioned to me that your work maps the “end of analogue”. Can you elaborate?

In 1991 I produced my first piece that was based on a world map. By 1995, I completed World-View: the G7 Suite for Eyelevel Gallery when Halifax hosted the G7 Economic Summit. In it, world-maps from each of the G7 nations were featured with encaustic overlays on Plexiglas of their national flags, a blatant tribute to Johns’ American Flag. Except, as noted in the exercise, each centre of the world and framing parameters was different to favour the publishing nation’s place in the world.

Paper maps and their ‘modernist’ framing devices became increasingly irrelevant shortly after when we entered the new realm of the world-wide web and the evolution of Google Earth and digital, satellite mapping. Of interest to me is the military pedigree of the digital technologies and the colonization of the world through remote visualization. The writings of Paul Virilio were important to me at the time considering that, in the new era of smart bombs, any site on the planet that can be ‘acquired’ through technological, visual means can also be destroyed by remotely launched missiles. Most paper maps that are published today are no longer functional geo-spatial tools but quaint, anachronistic artefacts that can, for example, map the craft breweries of a region.

Business envelopes from Pressure Today held, for example, the monthly round of financial statements, domestic invoices, charity requests and art-world promotions. By 2008, these delivery tools were disappearing in favour of on-line banking and internet-based economic solicitation and event promotion.

Written notes left for family members and/or co-workers were replaced in the smart-phone era with text messaging. The communicative power of scaled handwriting and gesture is now subject to standardized fonts and a slate of emoticons.

Paper shopping and ‘to-do’ list are now entered and archived on cell phones. The material culture of inter-human relationships is disappearing. Over the past 25 years, I never intended to capture the waning presence of physical maps and envelopes and other paper-based modes of communication.

What’s next?

After months of experimenting, I am committed to working on 6” square panels that are located on a grid 2” apart from each other. 6” is the perfect size for the range of encaustic applications that I have been playing with for the past few decades. As conceptual frameworks, I will be adding circles back into the grid. As previously mentioned, I consider the grid as a modernist spatial device that generates a matrix of sorts whereas the circle, as a graphic device, lacks corners, x/y coordinates and is not directional. Semiotically, circles and grids create a graphic tension between “O” and “X”, 2D representations of the world and lines of longitude and latitude, scopes and crosshairs.

I will return to human-scaled works that do not have square silhouettes. Image content will continue to be a mix of the minutia of my personal life as captured in paper envelopes, notes, lists and ephemera juxtaposed with larger geo-physical maps and digital weather records. Lurking in the mix will be subtle codes that allude to the reality of a world under the influence of global, corporate and military interests. These are themes that have woven throughout the decades of my practice; at this point in my life, I intend to ‘curate’ these subjects into nuanced and layered portraits of my life in 2017 and beyond.