You recently performed at your group exhibition opening at Y+ contemporary Artist-run space in Scarborough, where you tied cable knots with the visitors. You described the knots as a “labour residue”; can you explain what you mean by this?

When I first showed the cable knots as part of my MFA thesis exhibition at Anna Leonowens Gallery, I decided not to perform in person—to not tie knots in the gallery space. At the time, I wanted to see how the knots functioned as sculpture and performance residue. I felt (and still feel) that the weight of labour and traces of the labourer reside in the knots—but I suppose that can be said of anything ‘made’.

This March at Y+, Tiffany Schoffield curated a group show with work by Deirdre Logue, Anique J. Jordan, and I. We are all artists who claim Scarborough as their home in some way. Tiffany invited me to perform/workshop the knots at the opening reception, and I was delighted to have that opportunity to expand and experience the work in a new way. To facilitate the workshop and help with the learning curve of tying knots, I illustrated some diagrams and offered them as take-way instruction zines. The experience of tying knots with a community of friends and strangers was really warm and lovely— challenging, intimate, and rewarding. Participants were able to take away their own cable knots or leave them in the gallery to be part of the exhibition. Many people donated their knots for display in the gallery.

In our last interview together, you discussed being an immigrant to Canada when you were two and a half years old and growing up bilingual (Chinese and English) in a Chinese-speaking home. Last fall (2016), you performed by writing a letter to your father where you tried to communicate meaningfully with him using the basic Chinese you remembered. Can you tell us the context of this performance, and how this loss and relearning of language impacted your expectations of this conversation with your father?

I made a new performance in the fall of 2016 for 7a*11d’s International Festival of Performance Art, held every two years in Toronto. In that performance, How I can—well-enough (or showing my work), I set out to write a letter to my father, translating my Chinese thoughts into English words, then translating the English words into Traditional Chinese writing. I am fluent enough (with limited vocabulary) when speaking/listening to my parents in Mandarin and Cantonese. Growing up, my parents insisted that I speak Mandarin with my mom, and Cantonese with my dad. I also attended 9 years of Chinese school, but retained very little in terms of reading and writing—due to my resistance/reluctance to continue on (regrets, I have a few).

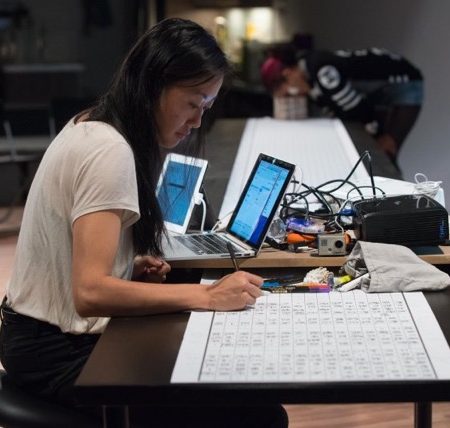

For the performance, I used a variety of online translation tools to help me find the exact words and phrasing, as I painstakingly assembled written phrases and sentences that sound like my own Chinese voice. There was a lot of trial and error, plugging in English variations and having the translator read them aloud for me to hear and select from.

I chose to write a letter to my father for the performance, because our conversations lack intimacy, or any emotional knowledge of each other. The durational performance lasting five hours gave me a lengthy period of time to be thoughtful, to research, and write a coherent letter in Chinese. I chose this as the remedy to my father and my habit for brevity when attempting to communicate verbally in Chinese. Given enough space and time, I slowly found the many things we rarely say (or have never said) to each other. It was emotional and scary to have my mind touch down on some things that I wrote. I have not given him the letter yet. It’s hard to give such a loaded letter to my father, especially since he does not expect it. He is not yet aware that I made this work about him. My father is not involved in my art practice, although my mother has been very involved.

Much of your work shows a determination to include your Chinese heritage, in practice and aesthetic, such as the series (dis)comforted where you interpret a block of dried noodles in knit and wrap them in ramen plastic packaging. This series and also your cable knot series recall nostalgia, and a yearning for ‘home’. Are you incorporating technique from memory, or do you want to relearn and master traditional skills as a way to reconnect lost or broken narratives from your personal history?

I’ve found that I’m always relearning something, and usually in a roundabout DIY kind of way. I spent a lot of time alone as a child, so I had to be resourceful to stay entertained. I often studied any available instruction books (most were in Chinese or Japanese so I had to rely on numbered diagrams), and the Internet when I had access to it at school and at home in the 90’s. Learning can feel like a cumulative practice, but what I found over time was that I’ve lost as much knowledge as I’ve gained over the years. It’s strange to relearn Chinese through English language and digital translation tools, when Chinese was my first language upon arriving in Canada. It’s even stranger that I can ably, albeit very slowly, re-teach myself things that are so rooted in history, language and tradition, using non-traditional and unconventional resources.

Some of your work is painstaking, controlled, and laboured, like Finational for instance in which you explore themes of loss, time and death by weaving a burial flag using newspapers, and pointing to the global economic system that caused the latest recession. You mentioned to me the desire to expand your practice from being slightly melancholy: why?

I struggle to buoy myself sometimes. I have a history of clinical depression, and I’ve heard and have also seen that much of my art feels melancholic. I use art to help me cope, but coping also helps me art. So seeking balance for my mental health has been very important. I used to paint, but it wasn’t right for me. I would paint sad paintings about sadness, and stay sad about it. It wasn’t very helpful or interesting (to me or anyone else). I discovered a world of possibilities in time-based and performance practice, and slowly built my own vernacular that embraced misunderstandings, failures, and nonsense. I try to employ strategies for control, while also allowing for chance in each project or work.

You are a compulsory list-maker, and say that this act is somewhat inspired by Chinese instructional books and diagrams. How do you incorporate list-making into your practice?

Every project involves making at least a few lists. To-do, materials, packing, updated to-do, due dates, budgets, most updated to-do, etc. The appearance of order helps me move forward, so it’s really a practical strategy to help me stay focused. Yes, instructional books and diagrams have been a major part of how and what I learn, and how I’ve learned to learn (usually relying not on the text, but mainly on numbered figures), so there is a relationship between those early experiences and my own compulsion to write/organize instructions to help me find solutions. In my teens and early adulthood, I worked a lot of administrative and office jobs and found that those skills translate easily into my life and art practice. I’ve started to use written and drawn structures directly in my recent work, that take the form of printed matter, fillable workbooks, stationary, performance materials/props/residue.

What’s next?

Tops on my outstanding to-do list is to edit video documentation from the 7a*11d performance from last fall, and settling into my studio practice in our new home in Halifax—My partner and I moved in at the end of last summer and I am very slow at adjusting to life in new spaces and places. I’ll probably make a workbook or performance, or several, to help me with that.